By restricting the export of gallium and germanium — key elements in cutting-edge military technologies — China appears to have taken aim at the U.S. defense industry in its economic tit-for-tat with Washington.

But the impact of the latest curbs will likely be limited, experts say, as the United States is already looking for alternative supply chains.

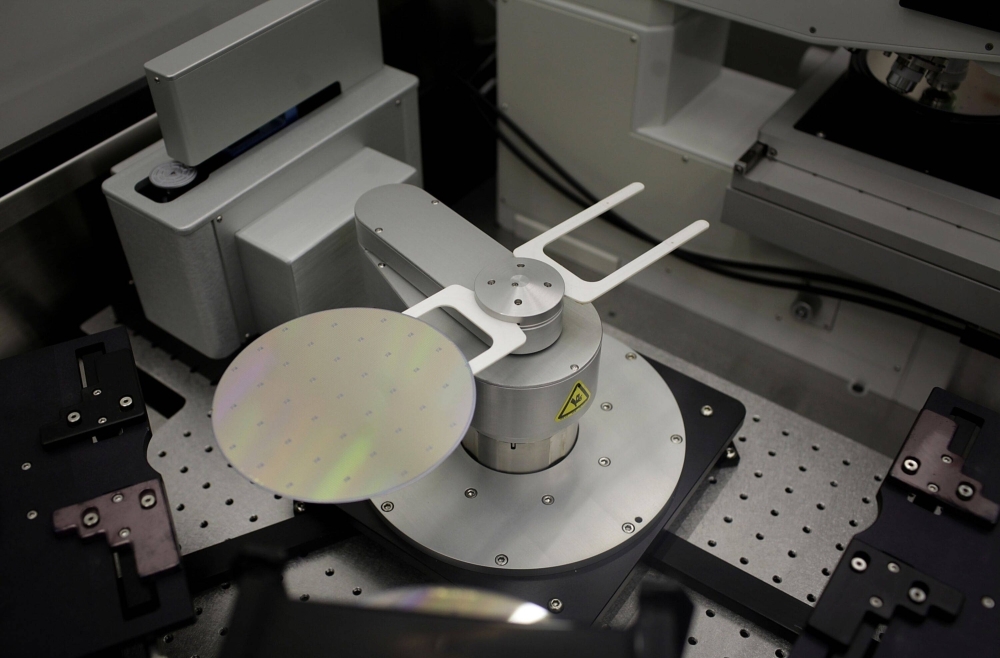

Announced in early July and implemented on Aug. 1, Beijing’s export controls apply not only to gallium and germanium but also to their chemical compounds, including gallium nitride (GaN) and germanium dioxide, which are essential to the global supply chain for dual-use applications such as advanced semiconductors.

This is crucial for the manufacturing capacity of the Western defense industry, particularly given GaN’s use in electronic warfare and communications equipment as well as next-generation missile defense and high-energy radar systems.

“GaN is revolutionizing radar capabilities, allowing new radar modules to track smaller, faster, and more numerous threats from nearly double the distance,” said Brian Hart, a fellow with the China Power Project at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Washington and its allies are also incorporating GaN-enhanced radars into critical platforms, including F-35 stealth fighters, missile defense systems and advanced naval warships, he said.

Germanium is also used in various defense applications, including high-end semiconductors and night-vision systems. The element is so important that the Pentagon has maintained a strategic stockpile.

These critical metals are not extracted directly. They are byproducts of refining other metals. Gallium is a byproduct of processing bauxite and zinc ores, while germanium is formed as a byproduct of zinc production.

China said the recent export controls — covering a total of 38 products — are necessary to safeguard national security, but experts believe this is a way for the country to hit back at U.S. and allied efforts to limit Beijing’s access to advanced technologies, including semiconductors.

A Gallium Arsenide semiconducting wafer | BLOOMBERG

The move also highlights China’s dominant position in the global production of these minerals.

Beijing dominates production of these two metals not because they are rare, but because Chinese companies have been able to keep their production costs fairly low and manufacturers elsewhere haven’t been able to match the country’s competitive costs, said economists at ING Bank.

And as China has been increasing its share of production, other countries, including Germany and Kazakhstan, have reduced their output as production can be costly, technically challenging, energy-intensive and polluting.

That said, gallium and germanium are so important that they are on both the U.S. government’s and the European Union’s lists of “critical raw materials.” The restrictions have thus raised concerns among the U.S. and its allies about potential supply disruptions.

Indeed, this wouldn’t be the first time Beijing has leveraged critical minerals or rare earths for political purposes.

In 2010, for instance, China blocked the export of rare earths to Japan after the captain of a Chinese fishing boat was arrested near the Japanese-controlled, Chinese-claimed Senkaku Islands, leaving Japan’s electronics and auto industries suddenly without an essential resource for several weeks.

China accounted for 98% of worldwide primary low-purity gallium production in 2022, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, with its dominant position being a byproduct of its influence over aluminum production.

China was also the world’s leading producer of germanium last year, with the country controlling 68% of global refinery production, noted ING Bank, with the rest of processing spread across Europe and North America.

Beyond these two elements, China has cemented itself as the leading supplier of many of the minerals that are crucial to the modern economy.

In fact, of the 47 materials for which the U.S. net import reliance is greater than 50%, China is either the — or one of the — leading import sources for 25, according to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission in its 2022 annual report.

Still, while China is the world leader in gallium production, it is not the only player in the global supply chain.

Given that the mineral is dual use, and that there is a network of suppliers that are not reliant on China, “the short- and long-term threat to the Pentagon and the defense industrial base (from the export restrictions) is likely minimal,” CSIS experts said in a report, emphasizing that China “will not be able to completely cut off access” to these minerals.

“China’s lack of a chokehold on the global supply chain may undercut the effectiveness of its sanctions to such a degree that they may be mostly symbolic — by intent or otherwise,” they said.

A container ship near Tianjin port in Tianjin, China, on June 30. Announced in early July and implemented on Aug. 1, Beijing’s export controls apply not only to gallium and germanium but also to their chemical compounds. | BLOOMBERG

In terms of alternative suppliers, experts point to Japan as a major player in worldwide gallium production, noting that the country has three methods of production.

First, Japanese companies can import lower-purity gallium and refine it, which will still be possible despite Chinese export controls, as China only has a 22% share of Japan’s imports of gallium and other critical minerals.

Second, they said, Japan produces gallium by recycling globally available scrap; and third, the country also has its own primary gallium production, carried out by the DOWA Metals and Mining Company using byproducts of smelting zinc imported from Mexico, which is outside of Chinese control.

According to Eugene Gholz, associate professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame, other countries have also been producing the material, including South Korea, Canada and Ukraine, meaning that the know-how to produce gallium is not limited to China.

He also pointed out that, even before China imposed its export controls, several other producers, including in Germany, had announced plans to return to gallium production as a result of increased demand.

There is currently no gallium production in Australia, which was previously a major producer, but experts say favorable market conditions could help spur a revival of mothballed facilities that could lead to a surge in capacity.

Meanwhile, the U.S. is using Title III of the Defense Production Act — which targets investments to mitigate industrial base shortfalls and risks, and expand defense production capabilities — to boost domestic mining and processing of critical minerals.

For instance, a senior U.S. Department of Defense official told The Japan Times that the Pentagon will be prioritizing awards for gallium and germanium by the end of the year, focusing on recovery of these materials from existing waste streams of other products.

“Our five-year plan for gallium and germanium is to begin drilling and extraction so we have full ‘rock to product’ capability in the U.S.,” the official said.

He also emphasized that the Pentagon will be using “all available authorities” to address these challenges as well as to incentivize and coordinate with industry partners as “we seek to ‘on-shore’ and ‘ally-shore’ our most critical capabilities and ensure access to raw materials.”

U.S. defense demand, however, accounts for only a fraction of the country’s total demand for these two minerals. This means that if Washington chose to prioritize defense uses of the minerals, “it would likely find enough non-Chinese material to continue defense production,” Gholz stressed.

Even after a period of friction and reshuffling in the global market, it is quite likely that there will be plenty of non-Chinese gallium and germanium to go around for total U.S. demand, he said.

Analyst Hart argues that the impact of China’s latest export controls will depend on how strictly Beijing applies and enforces them.

In the short term, both civilian and military end-users of these minerals will probably not suffer too much, he said, arguing that while there have already been price spikes and there may be continued price fluctuations, some companies have a few months of stockpiles that will help them weather the storm for now.

The bigger question, he said, is the long-term impact, and what happens if there is a major U.S.-China crisis.

“If China really wanted to escalate, it could ramp up restrictions on these critical minerals, or include curbs on other materials or compounds, to really choke off access,” Hart said.

“That would impose costs on China too, but in a crisis, Beijing may calculate that the costs are worth it.”

Source: The Japan Times